(Editor’s Note: This article was written by Kate Preziosi ’10)

The confocal microscope that lives in a narrow, nondescript room in Olin Hall is proving to be an invaluable new addition to the Biology Department that will open doors for student and faculty researchers alike.

The microscope, secured through a $500,000 National Science Foundation grant last year, can record cellular development and reconstruct three-dimensional images that will allow łÉČËÍ·Ěő scientists to study cells and organisms in their entirety instead of a two-dimensional plane.

This system is of growing importance in the research world, but is not yet widely prevalent at undergraduate institutions.

Assistant Professor of Biology Jason Meyers, who wrote the grant, has been studying the development of sensory cells and neurons since he was an undergraduate at Williams College.

The microscope is playing an important role in the research he is currently conducting with students such as J.T. Crepps ’10 to better understand retinal stem cell development in zebrafish.

“This project is looking at whether cells transplanted from the brain can change their fate when they are placed in the retina,” explained Meyers. “[J.T.] has some interesting data to demonstrate that the cells can change their fate, and adapt to the transplant.”

|

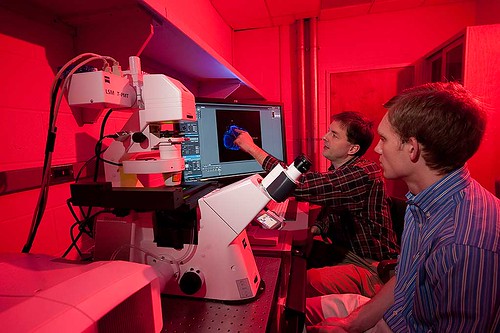

| Jason Meyers, assistant professor of biology, (left) works with another of his research students, Pierson Ebrom ’10, on a confocal microscope in Olin Hall. (Photo by Andy Daddio) |

“The fish retina and human retina are very similar. But stem cells in fish make developmental decisions that they don’t in humans. We want to perhaps understand ways of stimulating these cells to act differently.”

Using the confocal microscope, Meyers and Crepps can observe certain cells injected with fluorescent dyes and proteins. The microscope’s lasers will scan across the entire sample, identifying these cells with bright blues and greens that allow them to watch how they develop overtime. These capabilities are a departure from the standard microscope that illuminates universally across a sample.

These kinds of joint research experiences are part of what attracted Meyers to teach at łÉČËÍ·Ěő as opposed to a larger research institution.

“My whole trajectory of learning has been in a liberal arts climate,” he said. “I interacted with a wide variety of professors in very much the same way students do here at łÉČËÍ·Ěő. You know, getting invited to their houses for lunch and dinner, meeting them at the snack bar, and having them really interested in what you’re doing. It made me want to have that effect on my students here.”

Meyers was impressed with the academic atmosphere at łÉČËÍ·Ěő even before becoming a faculty member. During the interview process he taught a seminar to a group of students and professors, but spent the entire time discussing his research with the students.

“It really impressed me that not only were the students so engaged in asking good quality questions, but that the faculty were satisfied to let the students do this. The students here just love to learn. They’re so driven and motivated that it makes it fun to teach.”